The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of conflicts which saw Napoleon’s French Empire pit itself against the European powers. The conflict revolutionised warfare and introduced conscription, in order for nations to build armies large enough to compete against Napoleons’ military machine which had conquered most of Europe. The French dominance in the field began to wane following their disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812, causing a retreat which cost the lives of countless men. Napoleon was defeated in 1814, and then again in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo after a brief return to power.

The Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday, 18 June 1815, near the village of Waterloo, south of Brussels, in what was then the Netherlands. A powerful French army, under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, was defeated by an Anglo-allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington, which was combined with a Prussian army under the command of Gerhard von Blücher.

The defeat at Waterloo ended Napoleon’s rule as Emperor of France, and marked the end of his return from the exile which had been imposed upon him after the Peninsula Wars. King Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne, and Napoleon was exiled to Saint Helena where he died in 1821.

Several men from west Wales are known to have fought at Waterloo, including Thomas Skeels, of Laugharne, but the most famous of them all was General Sir Thomas Picton, who was a trusted aide to Wellington. Picton is commemorated by the fine Picton Monument obelisk in Carmarthen, and also by a memorial in his home village of Rudbaxton.

Sir Thomas Picton

Thomas Picton had been born on 24 August 1758, the seventh child of Thomas Picton, and his wife Cecile, née Powell, of Pyston, Rudbaxton, Pembrokeshire.

In 1771 he obtained an ensign’s commission in the 12th Regiment of Foot, but he did not join the regiment for another two years. The regiment was then stationed at Gibraltar, where he remained until he was made captain in the 75th in January 1778. He then returned to Britain.

The regiment was disbanded five years later, and Picton quelled a mutiny amongst the men by his prompt personal action and courage, and was promised the rank of major as a reward. He did not receive it, and after living in retirement on his father’s estate for nearly twelve years, he went out to the West Indies in 1794 with Sir John Vaughan, the commander-in-chief, who made him his aide-de-camp and gave him a captaincy in the 17th foot. Shortly afterwards he was promoted major.

His career blossomed during several campaigns in the West Indies, and he was made Governor of Trinidad, a post he held until resigning the post following allegations of brutality and torture, and Thomas returned to the army. Again he carried on making a name for himself, and in 1810 was given command of the 3rd Division of Wellington’s Army in Spain, during the Peninsula Wars. Yet again Thomas excelled, especially during the Battle of Vitoria and in the Pyrenees, and at the end of the campaign was honoured by Parliament, before returning home to Iscoed, near Ferryside. Upon Napoleon’s return from exile on Elba, Picton, who was still at Iscoed, was called on by Wellington to take up a commission in the Anglo-Dutch Army.

Picton was wounded at Quatre Bras on 16 June 1815, two days before the Battle of Waterloo, but concealed his wound to retain command of his troops. At Waterloo, on 18 June, he was in command of the 5th Division, and was shot in the head and killed while leading a counter-assault upon Napoleons’ troops during the afternoon.

Picton’s body was buried in the family vault in St. George’s Hanover Square, and a proposal was made that a monument should be erected to him in Carmarthen. Lord Dynevor chaired the committee that organised the fundraising for the monument, which was designed by John Nash, the King’s Architect.

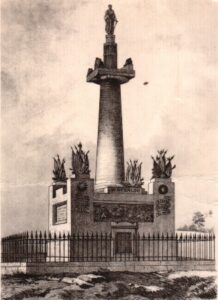

Work began after the laying of the foundation stone on 16 August 1825, and the work was carried out by the local stone mason Daniel Mainwaring. The original monument was designed to be 75 feet high, with an internal staircase leading to a viewing platform, with small cannon at the four corners. Above this rose a pillar which was topped with a statue of Picton.

At the base, there were panels, sculpted by Edward Hodges Baily, showing Picton’s exploits and his death at Waterloo, with inscriptions in English and Welsh.

The monument was finally completed and dedicated on 29 July 1828, and its dedication was marked by a civic procession which included sixty Waterloo veterans and the local Carmarthen Militia. The original memorial is shown in the postcard above.

Sadly within a few years this fine monument had fallen into disrepair, and the finely sculpted panels had begun to fall apart. (One of the replacements for these is currently held by Carmarthen Museum). The entire monument was dismantled in 1846, while plans began again for a replacement.

The new monument, which is what remains today, although slightly shorter than it was after repair work in 1988, was designed by Frances Fowler. Building work begun in 1847 on the same spot at the top of Picton Terrace, which was then the main road west out of the town. Below is a postcard view of the memorial taken during the 1960’s.

Fresh life was breathed into the memorial in the years immediately following the signing of the armistice on 11 November 1918, when a trophy WW1 tank was presented to the town of Carmarthen. This tank was located, for many years, at the foot of the Picton Monument, but was probably broken up for scrap some years afterwards.

The Parish Church at Rudbaxton contains a fine marble bust of the General, which is inset into an alcove in a wall in the Church. (The Church in fact contains several memorials to members of the Picton family, notably Major General John Picton, brother of Sir Thomas, who also fought during the Peninsula War).