Following the outbreak of the French Revolutionary war in 1793 plans were sent out by the British Government to the Lord Lieutenants of each county in Britain containing provisions of the raising of Bodies of Cavalry, to consist of Gentlemen and Yeomanry. These bodies would be locally trained and could be called upon for the suppression of riots.

On 19 April 1794, a group of Pembrokeshire gentlemen held a meeting at Lord Milford’s London house to organise the formation of the ‘Pembrokeshire Company of Gentlemen and Yeomanry Cavalry’, later known as the Pembroke Yeomanry. It was made up of two troops, each raised by a Captain, containing fifty men. Captain Sir Richard Philipps (Lord Milford) commanded the Dungleddy troop of men from the Haverfordwest and Slebech area while Captain John Campbell (Lord Cawdor) commanded the Castlemartin troop, from the district around Stackpole.

Meanwhile, local landowner William Knox had raised the Fishguard and Newport Volunteer Infantry in 1794 as his response to this call to arms and by 1797 his unit, now the largest in Pembrokeshire, came under the command of his son, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Knox.

The Castlemartin Troop was first called upon during the winter of 1796, parading on market days in the Pembroke district after disturbances caused by bread shortages. More serious events were soon to come.

The French general, Lazare Hoche, had devised a plan to aid Irish revolutionaries, where two forces would land in Britain, one in Newcastle and another in west Wales, while a third body, the main force, some 15,000 French troops, would land in Bantry Bay, Ireland.

In December 1796 Hoche’s main expedition arrived at Bantry Bay, but a severe storm scattered the ships and the French were unable to disembark, so Hoche decided to return home to France. During the following month, the force heading for Newcastle mutinied during another storm and they also returned to France.

The third force, however, continued with their task and on 16 February 1797 a fleet of four French warships left Brest, destined for west Wales. The force consisted of 1,400 troops from Seconde Légion des Francs, under the command of Colonel William Tate, a seasoned American soldier who had fought against the British during the American War of Independence.

The invasion force comprised four warships, under Commodore Jean-Joseph Castagnier, who had orders to land Tate’s troops and then rendezvous with Hoche’s expedition returning from Ireland.

The troops, a mixed lot, were well-armed and landed at Carregwastad, some three miles north-west of Fishguard, under cover of darkness on the night of 22-23 February 1797.

Soon after landing, some of the less disciplined troops deserted and began looting nearby properties, thus raising the alarm among the locals.

Thomas Knox was attending an event at Tregwynt Manor on the same night of the French landings. A messenger arrived on horseback from the Fishguard and Newport Volunteer Infantry, informing their Commanding Officer of the French landings, so he rode to Fishguard to mobilise his force and also summoned the Newport Division to march to Fishguard.

Lord Cawdor, captain of the Castlemartin Troop of the Pembroke Yeomanry, was stationed thirty miles away at his home at Stackpole Court, where the troop was encamped. He mobilised his troops and set off for Haverfordwest to join up with the Pembroke Volunteers and the Cardiganshire Militia, who were on exercise. Lieutenant-Colonel Colby of the Pembrokeshire Militia had summoned together a force of 250 soldiers.

At Milford Haven, Captain Longcroft mobilised 150 sailors and brought a number of cannon ashore. With a healthy force now assembled, command was given to Lord Cawdor, and the assembled force began advancing to Fishguard.

The French had by now moved inland and began occupying several farmhouses, but with the undisciplined looters now away from the main force, only about 600 French troops remained ready to fight, but they had taken up defensive positions on the rocky heights of Carngelli and Garnwnda. Knox arrived on the scene with his men only to discover that he was greatly outnumbered, so retreated with his men, meeting up with Lord Cawdor and his troops at Treffgarne. Cawdor then led the assembled force towards Fishguard.

Meanwhile the invading force was starting to fall apart. Many of the men were deserters and former convicts who lacked morale, and the French realised that with the departure of their fleet, they were in a precarious position.

Cawdor and his troops reached Fishguard at about 17.00. They now numbered about 600 men, armed with three cannon and marched up Trefwrgi Lane from Goodwick toward the French position on Garngelli. A French officer, Lieutenant St. Leger, had set up an ambush, however Cawdor had decided not to attack until dawn, so had luckily withdrawn his men back into Fishguard.

During the evening two French officers arrived at the Royal Oak, in Fishguard Square, where Cawdor had set up his headquarters. They wished to negotiate a conditional surrender, but Cawdor replied that he would only accept the unconditional surrender of the French forces, before issuing an ultimatum to Colonel Tate: he had until 10.00 on 24 February to surrender on Goodwick Sands, otherwise his troops would be attacked. The following morning, Cawdor’s forces lined up in battle order on Goodwick Sands. Up above them on the cliffs, the inhabitants of the town came to watch and await Tate’s response to the ultimatum. The locals on the cliff included a large number of women wearing traditional Welsh costume, which included a red shawl and Welsh hat which, from a distance, the French mistook to be the uniforms of regular line infantry.

Tate attempted to delay the surrender, but he finally realised he had no other option, and by 14.00 the French had surrendered and marched to Goodwick. After seizing their weapons, Cawdor’s men marched their prisoners through Fishguard to Haverfordwest, while Cawdor received Tate’s official surrender at Trehowel Farm.

Tate and most of his force were returned to France in a prisoner exchange in 1798.

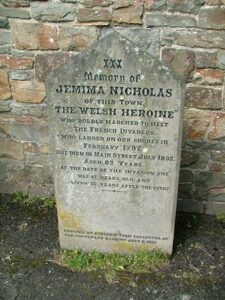

A local woman, Jemima Nicholas, had become a heroine overnight. She was the person who organised the local women and told them to wear their Welsh costume, as she had realised how similar they would look to soldiers from a distance. Cawdor had utilised this extra force by having them march up and down across the heights overlooking the beach, to make the French think they were more troops. She also reputedly captured a number of French soldiers herself and locked them inside St. Mary’s Church in Fishguard.

Jemima Nicholas was the daughter of William and Elinor Nicholas of Llanrhian, and was baptised in Mathry in 1755. She died in 1832, aged 82, and is buried in St. Mary’s Churchyard.

Jemima Nicholas’ Headstone

Meanwhile the French invasion fleet had also met with misfortune when it hit bad weather in the Irish Sea. Two Royal Navy ships, HMS St Fiorenzo, commanded by Sir Harry Neale, and HMS Nymphe, commanded by Captain John Cooke, encountered La Resistance and La Constance on 9 March and after a brief exchange of cannon fire, the French ships surrendered. One ship, Le Vengeance, escaped to France. The invasion had been a total disaster, and the last time an enemy invasion force would attempt to land in Britain.

In 1897, on the centenary of the battle, a memorial stone was erected to mark the defeat of the last invasion of Britain. The stone stands on a low rubble stone setting on a summit overlooking Carregwastad Point. The stone itself is almost six feet high and on its south face is inscribed:

1897

CARREG GOFFA

GLANIAD Y FFRANCOD

CHWEFROR 22. 1797

MEMORIAL STONE

OF THE

LANDING OF THE FRENCH

FEBRUARY 22. 1797

In 1853 Queen Victoria bestowed upon the Pembroke Yeomanry the battle honour ‘Fishguard’. It was the first battle honour awarded to a volunteer unit, and the first, and only, battle honour to be awarded on the British mainland.

This battle honour, FISHGUARD, is proudly displayed on the cap badge of the Pembroke Yeomanry to this day.

Pembroke Yeomanry Cap Badge

The Pembroke Yeomanry went on to gain further honours, especially during the Boer War, the Great War and in World War Two. More can be found about them by visiting the Pembroke Yeomanry page of this website.