Over the years Laugharne has always had very strong links to the sea. Situated on the confluence of the Taf and Corran rivers, the site was seen as ideally placed by people as far back as the Iron Age, when the hill-forts on Glan-y-Mor and Coygan were built. The Romans saw fit to build a fort on what is now the site of Laugharne Castle, to guard the waterway.

During the Norman invasion, a stone castle was built on the site of the old Roman Fort and, modified over the ages, still stands today.

The castle overlooks the Green Banks, Common Land, and the pill, where Laugharne seamen anchored their sailing ships and plied their trade around the world, even bringing back tobacco from Virginia.

The outer part of the estuary, Carmarthen Bay, was notorious for shipwrecks over the ages and there are reportedly around 200 to 200 shipwrecks around the bay. It was not uncommon for local fishermen and cockle pickers to find human remains on Laugharne Sands and the Strand following such shipwrecks, and these sailors were usually buried in the Sailors plot in St. Martin’s Churchyard.

Coaster ‘The Peggy’, of Laugharne (8 Oct 1836)

On Saturday 8 October the Laugharne registered Coaster The Peggy left Llanelli for Carmarthen with a cargo of coal and block tin. A heavy gale had come in on the previous day, sinking several vessels around the west Wales coast, and Peggy was to be no exception, when she was driven onto Laugharne Sands that afternoon.

Her Master, William Hughes and all of his crew, were very lucky. They all managed to reach the safety of the beach then managed to get help off some local farmers, who came down to the beach with their horses and carts and managed to salvage most of the cargo. The ship was destroyed by the waves during the night.

A sister ship, The Friends’ Goodwill, making the same trip with a cargo of coal for Carmarthen Tin Works, was lost in ten fathoms of water, along with her Master, David James, at the entrance to Carmarthen Bar the previous day.

Coaster ‘Sarah Ann Treharne’, of Laugharne (8 Oct 1836)

Among the earliest recorded shipwrecks, though most likely not the first, was the Coaster Sarah Ann Treharne, which was owned by John Griffiths, of The Strand.

She had a busy year, having been recorded on a regular basis sailing to and from Llanelli carrying grain, sometimes accompanied by other Laugharne boats, the St. Clears Castle, The Betsey, and The Peggy.

During the same October gale which had sunk The Peggy, the Sarah Ann Treharne was at anchor in Laugharne when she broke her ropes and began to drift. Her owner, Master John Griffiths, ran across the Strand and climbed the walls of Island House, before attempting to jump onto the deck of his boat to try and save her. Sadly, he mis-timed his jump and drowned at the foot of the Castle.

John was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend Jasper Harrison on 16 October 1836. Reverend Harrison later drew this picture of the wreck:

Schooner ‘Gem’, of Hull (7 Jan 1886)

The Gem was a 77-ton schooner which had been launched at Burton Stather in 1859 and was registered in Hull. Captained by William Taylor, Gem traded around Britain, France and the Mediterranean.

On 1 January 1867, Gem set sail on a voyage from Greenock to Southampton carrying a cargo of pig iron and machinery. On board was Captain Taylor and his wife, the mate Daniel James, Henry Harveston, William and Patrick McBride.

As Gem sailed through St Georges Channel, the passage from the Irish Sea into the Atlantic, on 7 January the schooner was caught up in a westward gale which drove it east. Losing all but one of her sails, Captain Taylor decided to head for Milford Haven, but in the terrible conditions, he mistook the Caldy Island light for St Anne’s light and, as a result, Gem ran aground on Carmarthen Bar, near the Ginst Point, at around midnight.

The crew set alight an iron cooking pot filled with tar and turpentine as a distress signal, and tied themselves onto the cross trees to attempt to ride out the storm. Sadly by daybreak, Captain Taylor, his wife and two crewmen had drowned, their bodies reportedly being terrible mangled by the breaking waves. Only Daniel James and Henry Harveston were still alive to tell of the terrible tale.

The stricken schooner was spotted during the morning and the Ferryside lifeboat, ‘City of Manchester’ was launched. The crew came across a terrible sight, but managed to rescue the two survivors.

The story is told in the ballad ‘The Night upon The Mast’, which was written by Reverend Jasper Nicholls Harrison, of Laugharne and was printed in 1868.

They hoped their moving forms, though dim,

Upon the mast descried,

Might tell of life in jeopardy,

Amid the angry tide.

And so it chanced – a fisherman

Far scanning with his glass

The wreck-strewn water of the bay,

A vacant hour to pass.

Spied one dark speck, some three leagues off

The breakers’ foam above,

Whereon there seemed at intervals

A thing of life to move.

The life-boat coxwain’s practiced eye

Confirms his doubtful guess-

It is the mast of shipwrecked bark,

And signal of distress.

Ring the alarm bell! rouse the place!

Collect our crew with speed;

Lend all a hand to launch the boat,

We’ll save them in their need!

Right heartily the villagers

Have lent a helping hand;

In half-an-hour they’ve dragged her o’er

A furlong of deep sand.

Two hours twelve pair of brawny arms

Have forced her through the wave,

As Britons only ply the oar,

Their brother man to save.

And now the watchers on the mast

Have cast away their grief,

Full well they know; life-boat’s rig,

And see their own relief

With grateful hearts, but feeble strength,

Their rescuers’ hands they clasp;

While one the shawl that saved their life

Still clutches in his grasp.

Brigantine ‘Mary Anne’, of Cardigan (14 Nov 1868)

Two years later the same stretch of sand was to claim another vessel. The Brigantine Mary Anne, of Cardigan, was sailing from Swansea for Dieppe, in ballast, when it got caught up in a storm and blown onto Laugharne Sands on Monday 14 November 1868.

The stricken boat was spotted at about 14.00 and a number of men from the neighbourhood of Laugharne rushed down to the sands to attempt to rescue the crew of the stricken vessel.

With the boat now beached and waves breaking over her, the captain and crew took to their boat at about 15.00 but the small craft was rolled over time and time again in the rough seas and out of seven men aboard Mary Anne, only one reached the safety of the beach alive.

The locals watched in disbelief as to how quickly the sea tore up the Brigantine and reduced it to driftwood. Most of the bodies were recovered over the coming days. (The surviving burial registers for St. Martin’s Church start from 1873, so it is not known for certain if these men were buried in Laugharne).

The Jean Lawrence (Dec 1872)

During the first week of December 1872, locals walking along Laugharne Sands found a large amount of wreckage strewn along the beach. Among the scattered wreckage was part of a hull and sternpost, with the name ‘Jean Lawrence’ painted onto it. At least five vessels had been sunk by storms in the Bristol Channel that week.

No more information can be found of the Jean Lawrence.

An Unknown Sailor (Aug 1873)

On 29 August 1873 the body of a sailor was found washed ashore on Laugharne Sands, near Great Hill. The man, estimated as being around 60 years old, was dressed in blue serge with a cotton plaid shirt, with blue cloth trousers, grey woollen stockings and cassock boots. He appeared to have been in the water for about a fortnight.

His remains were buried in the Unknown Sailors plot in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend Jasper Harrison.

The Barque Teviotdale (15 Oct 1886)

The Barque Teviotdale had been built in 1882 and was owned by Helmsdale S.S Company. On 15 October 1886 she was sailing from Cardiff to Bombay with a cargo of coal, under the command of Master James Smith, when she became blown onto Cen Sidan Sands, near Pembrey, and was wrecked.

The Captain and eighteen men left by boats, but only two managed to reach shore and the rest were drowned. Another ten men stayed aboard the stricken vessel and were rescued by the Ferryside Lifeboat.

Over the coming days bodies of her crew were found washed ashore around Carmarthen Bay. The body of her Master, James Smith, was found on mudbanks in the River Towy and was brought to Carmarthen, while the bodies of two other crewmen, one later identified as the 20-year-old John Sherlin, of Greenock, were washed ashore on Laugharne Sands.

John Sherlin was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend Jasper Harrison on 15 October 1886, while the other man, who remained unidentified, was buried next to him on 1 November 1886, again by Reverend Jasper Harrison.

The French Barque Confiance (22 Jan 1890)

On Tuesday 21 January 1890 a heavy gale hit the coast of west Wales. Sailing along the coast, the French barque Confiance was some 20 days into her journey from Havre to Cayenne, when she began to get into difficulty. Her Captain decided to drop anchor off Raglen Point in an attempt to ride out the storm.

A fishing sloop from Tenby put off to render assistance but was waved away, so returned to the safety of Tenby Harbour.

On the following day the French Captain and his crew launched a boat from Confiance and attempted to land on the beach opposite Amroth Castle, but the boat overturned in the heavy surf and three sailors were drowned.

The crew returned to their ship later in the day and Confiance was safely brought into Tenby Roads. There were allegations made against the crew of the Tenby lifeboat soon afterwards, as to her lack of assistance to Confiance, but it was argued that the crew were ready to go to her aid, but as no alarm was raised, and the vessel was not in danger, they did not need to go out. The only mistake was that made by her Captain, by attempting to land his crew in heavy seas, which was the cause of the loss of life. If they had stayed aboard their ship, no-one would have drowned.

Her Captain, H. Robard, later claimed that his men had been scared by the actions of the Tenby fishing sloop and that the lack of a lifeboat had frightened his men into attempting to land at Amroth, pinning the blame on the sloop and on the Tenby lifeboatsmen.

At mid-day on Wednesday 29 January, Joseph Shankland, a carpenter from Laugharne, was walking along the shore by Great Hill Farm when he spotted the naked body of a man lying near the high-water mark. The body had the appearance of a foreigner, some five feet six inches in height, of a dark complexion, and full black beard. The only items of clothing were a belt and a scarf around his neck. A waistcoat was found further along the beach.

The man was later identified as a Frenchman named Moizeu of the French barque Confiance. He was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard on 1 February 1890 by Rev Jasper Harrison.

The Tug Secret (25 Oct 1892)

On 25 October 1892 the newly launched Tugboat Secret left Lytham, Lancashire for the Thames London, crewed by six men and with three passengers from London. Among the passengers was 19-year-old Walter Soundy, a son of the owner of the tug.

On the following day the Tug was rounding the Pembrokeshire coast when she was caught up in a severe gale and foundered. She was originally reported as overdue, but her status was soon changed to being missing by Lloyd’s of London. Nothing was known of her until bodies began to be found in local waters, when it was realised that the Tug must have foundered somewhere between Lundy and the Helwick Lightship and that all nine men had been lost.

A person unknown found drowned on Laugharne Sands four days later was identified as Charles Hankinson, of Freckleton, Lytham, Lancs. The 37-year-old was identified by a pair of clogs, a muffler and pocket knife and a pair of studs. He was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend Jasper Harrison on 1 November 1892.

Several weeks later another body was washed ashore on Laugharne Sands, in an advanced state of decomposition and with the head and hands missing. The body was identified by his wife Mary, through his clothing and some personal belongings as that of John Dickinson, of Freckleton, Lytham, Lancs, also of the Tug Secret, and was buried in St, Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend John Thomas on 6 February 1893.

The body of another man, Hubert Turnbull Pohl was caught in a trawlers net near the Helwick Lightship and brought back to Tenby; while another body was washed ashore at Cefn Sidan Sands, which was identified as Frederick William Eyre, a bookkeeper for Soundy and Sons, the owners.

Sailing Ship Australia (30 Mar 1901)

On Thursday 28 March 1901 the fully rigged ship Australia, under Captain Jebe, left Cardiff with a cargo of 1,900 tons of coal, bound for Rio de Janeiro.

The ship, with a crew of seventeen men, met heavy weather straight away and made for the safety of the roads for some hours before resuming its voyage. Just beyond Lundy the storm worsened and the Australia soon got into difficulties. Her sails tore to ribbons and the heavy seas swept over her decks. The weather continued all through Friday night and by Saturday morning the Australia had began drifting helplessly towards the dangerous sands of Carmarthen Bay.

Distress rockets were fired by Captain Jebe and at around 06.00 on Saturday 30 March 1901 the Australia hit the sands of Cefn Sidan and settled in the water. Jebe and his frightened crew climbed into the riggings to get away from the waves which were running over the hull of the ship and the cold water soon caused two men to lose their hold of the rigging and slip into the water, where they drowned.

The distress flares had been spotted and the Ferryside Lifeboat, under the command of David Jones, known as Dai Pilot (an uncle to Dylan Thomas) began to row out towards the stricken Australia. It took over two and a half hours of extremely difficult rowing to reach the ship, but once taken alongside, Jones managed to rescue all of the remaining fifteen crew, including Captain Jebe.

It took several more hours to get back to shore, but the now shattered sailors were taken to the White Lion Inn to be warmed up and fed, before being put to bed.

The crew of the Australia were mainly Norwegians, and David Jones was awarded a Silver Medal by the King of Norway for his heroic efforts to save the fifteen men.

The bodies of the two drowned sailors washed ashore on Laugharne Sands on Good Friday, 5 April 1901 and brought to the mortuary at Laugharne where they were identified as those of Benjamin Olarsson, aged 39, of Tonsberg, Norway and Igurman Juho Santamaki, aged 24, of Tamerfors, Finland.

Both men were buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend Atterbury-Thomas at 14.00 on Sunday 7 April 1901. Hundreds of people attended the service, to honour two men from a far-away country and Mr Broadwood, of Broadway Mansion, sent two beautiful wreaths to be placed on the sailors graves.

The Steam Ship Irene (10 Sep 1903)

The Steam Ship Irene was built in Glasgow in 1898 and was owned by Michael Murphy of Dublin. Sailing from Newport for Dublin with a cargo of 600 tons of coal, under the command of Master C. Gallagher, Irene went missing at some time during the great storm of 10 September 1903, with the loss of all her crew, including her Master and 13 men.

The wreck was later discovered upside down, at a depth of about eighteen metres, between Port Talbot and Porthcawl, and her Ships Bell was recovered by divers in 1992.

Some weeks after the sinking, two bodies were recovered from Laugharne Sands, presumed to be victoms of the SS Irene disaster. The first an unknown man, aged about 50 years, was buried at St. Martin’s on 1 October 1903 by Reverend Atterbury Thomas.

The second man, aged about 40 years, was buried in St. Martin’s on 1 October 1903 by Reverend Atterbury Thomas.

Unknown Sailor (Aug 1917)

Over the years hundreds of merchant ships have been lost around the coast of Wales, especially during the periods of both World Wars. The majority of the sailors aboard these ships were lost to the sea and as a result are commemorated on the Tower Hill Memorial in London. Walking around many churchyards in coastal areas of Wales, it is quite likely that you will come across the grave of a sailor who had been found washed ashore locally and buried in a Sailors Plot, either under a named headstone, or marked simply as an Unknown Sailor.

Some cemeteries contain the familiar white Portland headstone marking the grave of sailors who were casualties of war and were erected by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) to mark the last resting place of the poor sailor buried beneath.

Among many others around Wales, there are graves to Unknown Sailors of both World Wars in cemeteries such as: Angle, Dale, Tenby, Llanwnda, Granston, and Talbenny in Pembrokeshire; Colwyn Bay, in Denbighshire; and Llwyngwril in Merionethshire, which contains the graves of five unknown sailors who perished during the loss of H.M. Yacht Kethailes on 11 October 1917, as well as that of Second Engineer James Grieve, of the same boat, who died on the following day.

One such sailor was found washed up on shore opposite Great Hill Farm, Laugharne Marsh in August 1917. The body of the man, who was not identified, was buried a week later by Coroners Order at St. Martin’s on 15 August 1917 by Reverend J. Thomas.

The burial caused somewhat of an embarrassment to the County Council, which was reported in the Carmarthen Journal of 9 Nov 1917: “It is much to be regretted that whilst sailors are losing their lives daily to keep us supplied with food that local authorities should quarrel over a bill of £4 for burying the body of an unknown man washed up at Laugharne. Unfortunately, the bodies of unknown men are washed up on every coast of Britain just now.”

The County Council initially refused to pay for the cost of the burial, until being embarrassed to do so by newspaper reports such as the above.

Unknown Sailor – Domingo Mobile (1 Feb 1918)

On 8 February 1918 a local man walking at the Ginst Point spotted a small lifeboat which had run ashore. He was shocked to discover the bullet riddled body of a sailor lying in the bottom, and called the local Policeman, PC Hoare. An inquest into the death of the man was held by the County Coroner, Mr Thomas Walters, who found that the man had died as a result of a gunshot wound to the head. Among the papers in the man’s pockets was an Alien’s Registration Card, which had been stamped several times by the Carmarthenshire Constabulary and enabled the body to be identified as that of a Venezuelan sailor, Domingo Mobile.

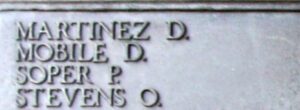

Domingo served with the Mercantile Marine aboard the London registered steamship, S.S. Sofie, which had been built in 1907. On 1 February 1918 she was en-route from Jersey to Cardiff in ballast when she was attacked in the Bristol Channel by the German submarine U-101. She was hit by gunfire from the surfaced U-Boat and went down with the loss of eight lives: Hubert Francis Burdett (Master), aged 22, of Frampton-on-Severn; C. Amesti (Fireman), aged 46, of Bilbao; John Bernard Harrington (Mate), aged 27, of Barry; William George Lippiatt (First Engineer), aged 56, of Bristol; Devanez Martinez (Second Engineer), aged 30, of Newport; Peter Soper (Fireman), aged 35, of Venezuela; Ormond Stevens (Able Seaman), aged 33, of Guernsey; and Domingo Mobile.

Domingo was thirty nine years old when he was killed and he was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard, Laugharne on 13 February 1918 by Reverend J. Thomas. Details regarding his burial were not passed onto the authorities, so after the war his body was assumed to have been lost at sea and his name was included on the Tower Hill Memorial, in London.

It was only after discovering the story of his death whilst researching my third book, Carmarthen in the Great War, that I discovered that Domingo’s burial had been recorded in the burial register at St. Martin’s Church, and this prompted me to carry out some more research on him in order to gather evidence to present to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, in order to gain Domingo a proper headstone. This evidence was presented to them over two years ago and they quickly accepted it, altering his details in their online Book of Remembrance to suit.

On Thursday 4 May 2017 the CWGC erected a ‘Special Memorial’ headstone in the Churchyard to commemorate Domingo, so after almost a hundred of years of lying in an unmarked grave, Domingo Mobile at last has a CWGC headstone to mark his last resting place.

The remains of another sailor from the SS Sofie, Pedro Soper, were recovered from Laques Fawr at Llansteffan around the same time and were buried in Llansteffan Churchyard, whilst on 3 April yet another body, most likely from the Sofie, was recovered and buried at Llansteffan also.

Steam Ship Maid of Delos (23 Dec 1922)

The Steam Ship Maid of Delos was originally built by James Laing, Deptford under the name Olympo, for the Plate Steamship Company, Rochester. In 1899 she was bought by the Deutsche Levante Line, Hamburg and renamed Delos, who transferred ownership to the Belgian Government in 1919 before it was finally sold to the Byron Steamship Company, London in 1921, and renamed Maid of Delos.

On 23 December 1922, Maid of Delos was on passage from Braila, on the Danube, in Romania for Dublin, carrying a cargo of barley, when she encountered problems while steaming through St. George’s Channel, south of Skomer. Her cargo shifted in the heavy seas and the ship began listing badly.

A distress call was sent from her, but nothing more was heard, until wreckage began to wash ashore at Angle the following morning. Twenty-six men had been lost in the sinking, and within the next few weeks many were washed up along the coast.

The bodies of four men were recovered from Laugharne Sands within the coming weeks, all assumed to be from the ill-fated ship:

The first body, of an Unknown Male later identified as William Edward Burge, aged 21 was buried by Coroners Order at St. Martin’s, Laugharne on 6 January 1923, by Reverend Picton Gordon Williams.

The second body, of an Unknown Male, aged about 35, was buried by Coroners Order on 7 January 1923, by Reverend Picton Gordon Williams.

The third body, of an Unknown Male, aged about 40, was buried by Coroners Order on 6 February 1923, by Reverend Picton Gordon Williams.

The fourth body, of an Unknown Male, mature aged, and reportedly very badly decomposed, was buried by Coroners Order on 24 February 1923, by Reverend Picton Gordon Williams.

Steam Ship St. Caradec (23 Dec 1924)

On the morning of Tuesday 23 December 1924, the French Steamship St. Caradec ran aground on Carmarthen Bar and sank with the loss of all hands.

Two members of her crew were washed ashore on Laugharne Sands, and at least one other man was washed ashore at Pembrey, a life-belt bearing the ships name around his body.

One of the men found at Laugharne was identified as the Master of the St. Caradec, Louis Alexis Rene Gueranton, a 39-year-old. He was buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard, Laugharne by Reverend W. J. Watson on 28 December 1924.

The second body, of apparently 5’ 6” in height, with long dark hair and a dark moustache, was of about 36 years of age. Evidently one of the crew of the St. Caradec, he was buried in St. Martin’s by Reverend W. J. Watson on 3 January 1925.

Inter-War Unknown Sailors Burials

In between the war years ships had become larger and most were steam or diesel powered, so the chances of shipwrecks lessened. There were three more instances of remains being found on Laugharne Sands following the sinking of the St. Caradec:

The body of an Unknown man, aged over 60, found drowned on Laugharne Sands was buried by Coroners Orders at St. Martin’s by Reverend W. J. Watson on 19 December 1927.

A human skull, found on Laugharne fore-shore, was by the order of the Coroner buried by Police in the Unknown Sailors section St. Martin’s Churchyard on 6 January 1930.

The remains of a human foot, still inside a sailors’ boot, which was presumably French, was found on Laugharne fore-shore and buried by the Police on Coroners Orders in the unknown sailors section of St. Martin’s Churchyard on 16 January 1935.

While the body of another Unknown Sailor was picked up on Laugharne Sands and buried in St. Martin’s Churchyard by Reverend S. B. Williams on 6 June 1935.

World War Two (1939-1945)

The body of an Unknown Soldier, measuring 5’ 6” tall, with a 40” chest, his left arm missing, clad only in boots (numbered), socks (with laundry marks), short leggings and remnants of khaki trousers, missing his upper teeth and two bottom molars, aged around 29, was recovered off Laugharne Sands on 29 August 1941. Sadly unidentified, the body was buried in the new Churchyard at St. Martin’s by Reverend S. B. Williams on 1 September 1941. The grave was marked by a Commonwealth War Graves Commission Headstone.

Unterofficer Willie Krock

On 12 August 1942 the body of a German Luftwaffe airman was recovered from the fore-shore at Laugharne. The body was identified by his dog-tags as Unterofficer Willie Krock, a 22-year-old from Frankfurt.

Willie was born in Frankfurt on 1 May 1920 and trained as a radio operator before being posted to Küstenfliegergruppe 106. The unit had taken part in the Battle of Britain, flying from bases in Brest and Cherbourg, equipped with the Dornier Do-18. By April 1942 the unit was based at Dinard and flew the Junkers Ju-88 bomber.

On 5 August 1942 Willie was flying aboard a Junkers Ju-88, Serial M2 + CK, piloted by Fw. Friedrich Grötzsch when the aircraft crashed into Carmarthen Bay. The aircraft was most likely part of a force sent to bomb Swansea, as at least one other German bomber was shot down that day, by a Beaufighter, and crashed into the sea off Swansea. Willie’s body was the only one recovered from the aircraft, the remains of the pilot and two other crewmen were never found.

His body was brought to St. Martin’s Church for the night and the following day was picked up by Airmen from nearby RAF Pembrey and he was buried in Pembrey Churchyard.

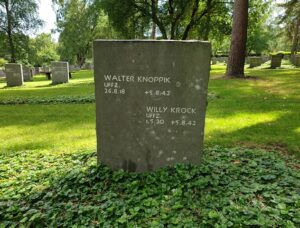

After the war, German burials in Britain were exhumed and re-interred at the massive Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, in Staffordshire. Willie lies in Plot: Endgrablage: Block 7; Reihe 8 Grab 208. Buried alongside him is another German airman, Walter Knoppik, whose Dornier was shot down in Swansea Bay that same day.